Social and Political Polarization in the United States

While it is widely felt that Americans have become much more strongly divided by politics in recent years, consistent evidence for such changes has been surprisingly elusive. For example, while much previous research finds that Americans have become better sorted by partisanship (for example, knowing that someone votes Democrat or Republican would give you a lot of information about that person’s likely opinions on particular issues, while this was less true in previous decades), there was much less evidence that Americans’ opinions on the issues themselves have become more polarized. This puzzle — that rising polarization seems like such a salient and consequential social fact, despite its apparent absence in the U.S. population — motivated me to examine opinion polarization through a different lens. In a 2020 article published in the American Sociological Review (link), I argued that polarization has increased in a way metaphorically resembling an “oil spill,” with politics seeping outward to encompass an increasingly broad array of social, cultural, and lifestyle topics — from beverage preferences to religious beliefs. I showed these changes by using the tools of network science to turn 44 years of nationally representative survey data into “belief networks” where we can systematically measure the relationships among hundreds of beliefs.

This study was in turn motivated by an earlier paper (link) in which Yongren Shi, Michael Macy, and I used a tongue-in-cheek title (“Why Do Liberals Drink Lattes?”) to examine a serious puzzle: Why and how does politics come to represent so much more than what we typically think of as political? We developed an agent-based computational model — a computer simulation in which artificial actors interact with one another using behavioral rules set by the researcher — to show how a polarized world of “latte liberals” and “bird-hunting conservatives” could emerge out of simple patterns of social influence in networks. While survey data provide detailed information about individuals, they rarely tell us much about the networks — family, friends, co-workers, etc. — that influence our politics, opinions, and lifestyles. The theoretical contribution of our paper was to suggest that accounting for these networks may hold the key to understanding otherwise enigmatic patterns of lifestyle polarization.

Networks, Social Influence, and Collective Behavior

I’ve worked on a diverse set of research projects that broadly deal with processes of social influence that play out in social networks, focusing on how these networked interactions influence societal outcomes ranging from voting to product evaluations. Two of my studies focus on the contact hypothesis, or the idea that interaction with people unlike ourselves should, over time, lead us to adopt more accepting attitudes. In my first published article (link), which appeared in Social Forces in 2013, I investigated the relationship between immigration and electoral support for far-right politics in France. Prior work had shown that areas with large immigrant populations also featured greater electoral support for the anti-immigrant National Front (since renamed National Rally) party. Re-examining this narrative, however, I found that the relationship depended crucially on the level of analysis. At the level of individual towns and cities – but not at the level of whole regions – immigrant population size was actually associated with less National Front voting. My 2018 Socius article (link) extended my interest in the contact hypothesis to a different social context: attitudes toward gay and lesbian people in the United States. This study was the first, to my knowledge, to use longitudinal and nationally representative survey data to test the effects of acquaintanceship with gays and lesbians on heterosexuals’ attitudes toward gay marriage over a span of several years.

I am also involved in multiple projects examining how (and when) our tendency to be influenced by the opinions of peers might either improve or distort our judgments. This work aligns with a theme from my co-authored 2015 article (link) concerning the unpredictable and path-dependent social dynamics that emerge when decisions are subject to social influence. In a paper that Minjae Kim and I published in 2022 in Organization Science (link), for example, we used an original data set of 1.6 million online beer reviews to show that social influence from previous reviewers of a product influences later reviewers in ways that materially affect evaluation and prestige of products in cultural markets. Several of my current ongoing projects deal with related themes.

Networks of Cooperation and Collaboration Within and Across Organizations

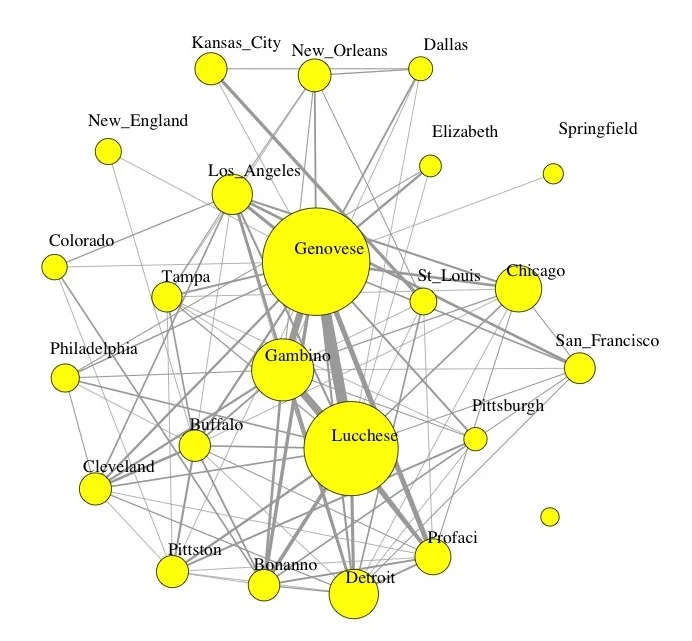

Across multiple topics, my research in this area brings new data and innovative methodological approaches to bear on fundamental theoretical puzzles. As part of my dissertation research on the Italian-American Mafia, I produced an original network data set with information on more than 700 mafia members and associates operating in various American cities at the middle of the 20th century. This research asks: How do organizations maintain internal solidarity and closure without compromising their access to diverse networks? The answer put forward in my 2017 Social Networks article (link) is that mafia families across the United States formed a “small-world” network structure combining high levels of in-group closure with extensive connections across groups such that a mafioso in Providence could reach one in San Francisco through just a few network ties. I also found that this integrated structure reflected a “division of network labor” wherein most mafiosi had none or very few ties beyond their own local family organization while a small number of “brokers” had many such ties. In a follow-up study published in Social Science Research (link), I show that these brokers were disproportionately likely to be ethnic non-Italians excluded from formal membership in a mafia family.

The “Mafia Network” dataset is relatively unique in the field of economic and organizational sociology for having individual-level network data both within and across organizations, in this case mafia families. These qualities have created opportunities for several fortunate collaborations. In a 2021 article (link) with Clio Andris and a team of graduate students, we used spatial network methods to map the geographic properties of criminal collaboration in mafia families. In another paper (link) with Andew Krajewski and Diane Felmlee, we examined how organizational hierarchies shaped network ties of criminal collaboration in mafia families.

Beyond the world of organized crime, my research in economic sociology centers more broadly on the emergence of economic institutions out of informal networks. My 2017 Rationality and Society article (link) with Victor Nee and Sonja Opper addressed a classic theoretical puzzle in sociology, political science, and economics: How do initially illegitimate organizational and institutional innovations emerge and diffuse despite legal risks and uncertain rewards? We presented a theory of endogenous institutional change based on positive externalities from cooperation in tight-knit networks. We further explored this theory with both an agent-based model and two empirical case studies: the rise of private manufacturing in the Yangzi Delta region of China — a context further explored from the vantage point of CEO networks in a 2017 Sociological Science article (link) with Victor Nee and Lisha Liu — and the diffusion of gay bars in San Francisco during the 1960s and 70s.

My 2020 Social Science Research article (link) with Victor Nee speaks to a puzzle that dates back to the work of Adam Smith and Emile Durkheim: how do industrial clusters evolve such that individuals become more specialized while the system as a whole becomes more diverse? We demonstrated a new approach to tracking the emergence and specialization of economic knowledge over time using the case of New York City’s tech startup economy. For this project, we analyzed about 75,000 online discussions taking place over a seven year period in a large tech professional association. We used natural language processing, network visualizations, and a multilevel panel model to show how members progressively sorted themselves over time into subgroups organized around specialized topics and interests, providing a unique empirical window into the real-time specialization of knowledge and interests in a major urban economic setting.

I’ve sometimes worked on other projects that don’t fit neatly into any of these headings, such as this paper (link) with Gary Adler and Jane Lankes about “aesthetic style” in objects of religious worship and this paper (link) modeling causal heterogeneity in the economic returns to military service.